The Hole

What about an experience causes you to commit it to memory?

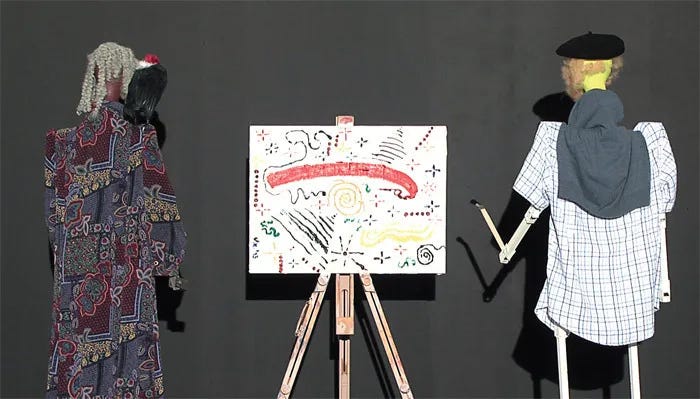

Any memory has a tangible, aesthetic quality, but many of my most memorable experiences have themselves been of a fundamentally aesthetic nature. One such experience took place in 2016, in the month of my 22nd birthday, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. It was then that I saw “Das Loch” [“The Hole”] by Harald Thys and Jos De Gruyter. Jointly a short film and an exhibition of art from within the film’s fictional world, “Das Loch” depicts a number of characters sharing their perspectives on life and on art: they’re sinister, they’re impassioned, and they’re fueled by the creative spirit in varying degrees. All of the characters in “Das Loch” are played by mannequins. And all of their voices are provided by text-to-speech generators.

“Das Loch” is from 2010, and looking back, it has certainly aged. I later learned that the mannequins are stylistically fundamental to the later work of Thys and De Gruyter. And many of those films look largely similar upon first glance. Still, there was one character in “Das Loch” that I found particularly unforgettable. He sticks out so much in the film, in fact, that his physical body was itself on display – in the gallery amid his artworks. His name is Johannes.

Johannes is a painter who believes in the universal power of art. He is the rival of a red macho mannequin who possesses an HD video camera. In the film, Johannes weeps in his computerized voice to someone named Hildegard. This is not Saint Hildegard of Bingen, of course, but rather Johannes’ wife, Hildegard. Nevertheless, the lamentations are psalmic in character: in the reference ‘Hildegard’ is already implied a sense of history, of spirit, of preservation through time. In a blurb about the work available on M HKA Ensembles, it is noted that “Johannes's empathetic wife Hildegard, in a role that reduces her to the female stereotype from film history, acts as the linchpin for her husband’s emotions.”

Few clips from the film can be found on the internet, and the full video is unavailable except where it is presently on display. Yet the impact which this exhibit had on me was so lasting that I remember it nearly a decade later. I can still hear that sad, computerized voice as it weeps out the anguish which Johannes wishes to express. It raises an interesting question, one of matter and form: was it the content of the speech which imparted the voice with its emotion? And even if the audio was somehow manipulated, it was only a computer; how could it ‘sound’ so sad?

I’m writing this more than seven years later, at the end of the year 2023. It’s my final week of unemployment living in Chicago before I start a new job. Since that day in 2016 I’ve worked a number of jobs, and I’ve worked each of those jobs in a number of industries. Right out of college I worked at a software company. Then I quit that job and I needed another one. I became a dishwasher. I did that until I was a bar back, and then a bartender, and then I worked into beverage sales and consultative roles within the restaurant industry. Eventually I gave that up for candle sales. The job I’ll start next week is also in sales. But now I’ll be in software again. It feels almost like I took a detour.

This week I’ve examined the continuum of my life as if it were a cavern. And a thought that comes to the forefront is this: I had a number of reasons for wanting to live in Chicago in particular. But what was it that I wanted so badly to do in Chicago?

The answer is this: what I am doing right now. And for that reason, I felt compelled to visit the Museum of Contemporary Art today. I wanted to reflect on the last 7 years, on how my thoughts have changed, and on how much has happened to me since that other impactful visit. I wanted to be deeply moved. But most importantly, I wanted to not expect a repetition. I’m old enough to know that that’s a recipe for disappointment.

The first exhibit I saw was one that was called Endless, and as it happens, it sought to be a depiction of the infinite. In the museum’s own words:

Impossible to convey in full, this idea prompts artists to acknowledge the limits of what they can depict and to develop open-ended ways of working. The artists featured in Endless use repetition, abstraction, and processes of change to poetically imply spatial, temporal, and spiritual expansiveness.

I often wonder if a work of art can still stir me as deeply as one could when I was younger. There’s certainly something much different about that feeling now, and now it affects me in much different ways. I’m aware that this is because I’m older and have more experiences of my own to draw from. But still I like to engage with art in the same way I would have then. I’ve had plenty of time to think about “Das Loch,” about The Hole. And it occurs to me that what I found so memorable was its expression of feeling and yearning, and this in spite of the formal constraints of the computers and the Styrofoam. [“The Hole”] possesses the timeless, and tireless, pang of lamentation. (Psalm 13:1: “How long, O LORD? Will you forget me forever? How long will you hide your face from me?”)

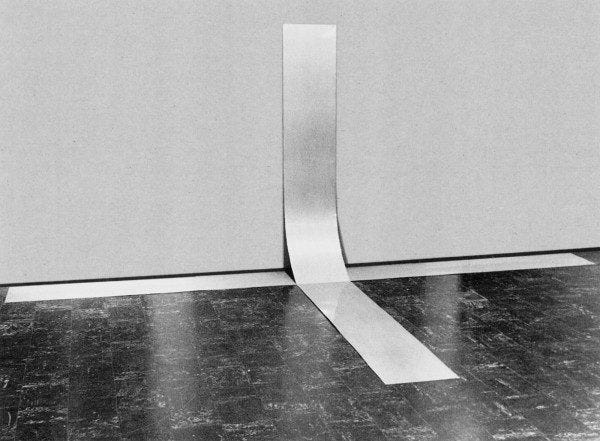

In the Endless gallery was a spatially-focused work by David Lamelas, entitled “The Situation of Four Aluminum Plates.” Consisting of just four flexible aluminum panels, “Situation” is an unfixed installation that changes its meaning depending on the space it inhabits. It compels the viewer to arrange themselves in accordance with how they feel it ‘ought’ to be perceived.

Like the anguished cries of Johannes, there’s something about how “Situation” is experienced that’s timeless, or which transcends time in favor of the infinite. It demonstrates how in all works of art there is embedded a characteristic of eternality. This is the very power of art over the individual, whose existence is finite and confined to the temporal realm. Aristotle suggests that something like ‘the eternal’ is itself form in the ultimate sense: while it can’t be known on its own account, it must first exist to make individual things knowable. Form is the staying-itself of the being-at-work. It’s what remains constant about a thing as it extends through time.

I am of the opinion that anyone can be deeply moved by any work of art, regardless of era, style, medium, or genre. The important thing is to remain open to its claim upon your perception, and necessarily to the manner of perception which most corresponds to its form. It’s this very relationship which in turn allows the work to render the viewer in its image. It’s why only after it’s passed out of frame that the work can become the entire content of thought. In his The Work of Art (1955), Stephen Pepper speaks of this tendency of the aesthetic experience:

The very consummatory structure of the situation draws you into the room to a position neither too near nor too far, where the colors and shapes are to be seen at their best. If there is a glass over the picture, you will move so that all glare is eliminated. In short, in a consummatory field of activity a person is drawn to the optimum condition of consummatory response with respect to the object…

By virtue of being embodied in space and in time, in other words, we are each endowed with the singular ability to experience a work of art exactly as it speaks to us.

At the time I saw “Das Loch,” I was writing consistently and self-publishing on my website. On my trip to Chicago in 2016, I started to write a story about discovering an identical self there, one which was previously unknown to me, coursing each day through the streets of the city. I never published this story, and even today it remains unfinished. Yet now that I’m doing in Chicago all that I wanted to do, I do in fact find this identical self, though not in space, but rather in time: I can peer back and I can feel his gaze upon me, as if in midair, sustained only by my holding it fixedly there. I cannot know his gaze, but I can know that it must exist—there’s no way I could be here unless it were so.